Accurate health data is an asset that has enormous personal and societal value. It contains intimate information about each one of us, that could allow us to make more informed decisions about our own health. When used for public good purposes it can allow health planners, researchers and innovators to respond more effectively to a population’s health, both within and across borders. However, many people are not aware of their rights[1] and many still consider their own data to be a by-product of the visit to the health centre[2]. Many health workers are not aware of the rights of patients and their responsibilities in relation to health data[3], and continue to treat it as a bureaucratic necessity, part of the increasing automation of the workplace. The lack of clarity over the rules and regulations that govern health data compound this situation.

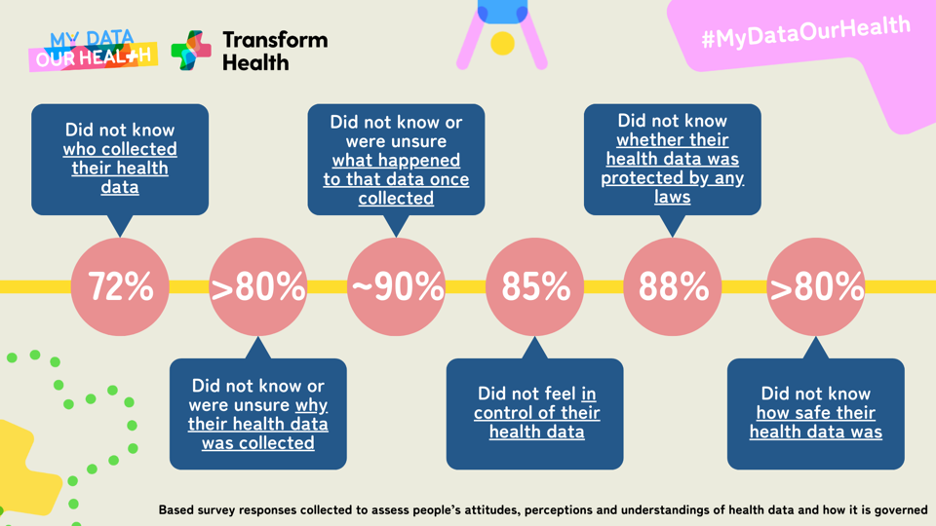

Transform Health conducted a survey to assess people’s attitudes, perceptions and understandings of health data and how it is governed. Over 2000 people responded, revealing low levels of public awareness and understanding.

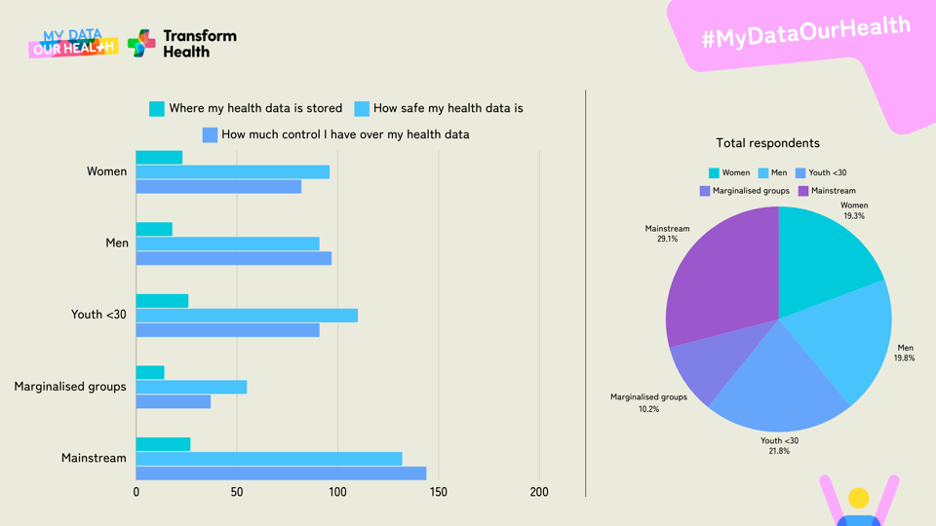

Most people were more concerned about how much control they have over their data and how safe it is, rather than where it is stored.

Figure 1. What aspects of health data matter most in East Africa

The My Data Our Health campaign

In January 2023, Transform Health and its partners launched the My Data Our Health campaign across seven countries in East and West Africa (Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, Tanzania and Uganda) to raise public and political awareness and galvanise action on health data and on the need for more effective legislation and regulation. The campaign was co-created with youth organisations and other partners and aims to build support for the development and endorsement of a global framework on health data governance (underpinned by the Health Data Governance Principles) by all countries at the World Health Assembly.

In April 2023, Transform Health commissioned research to get a deeper understanding of public and political perceptions and understanding of health data governance across six countries in East and West Africa (Kenya, Tanzania Uganda, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal). This revealed that the public conversation was limited to discussions around where the data should be physically kept and where servers should be located, with little attention paid to the issue of health data governance[4]. The mainstream media was not covering the issue, nor was it the subject of any attention from civil society and community groups[5].

Laws and regulations codify public values and concerns. If the public are not demanding political action on a given issue, politicians are less likely to dedicate legislative time to it. At the time of research there were no specific laws or regulations on health data across any of the six countries assessed (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Bening, Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal)[6]. General laws on data privacy and security existed and there was a plethora of regulations, strategies, policies and guidance on different aspects of health data, creating potential for regulatory fragmentation.

Twenty eight partners from seven countries across East and West Africa[7] organised a series of activities aimed at raising public and political awareness on the issue, from community engagement to high level meetings with politicians.

We developed the Where’s My Data? campaign action as a way of making the issue relevant to people’s personal experience. This simple action invites people to go to their health provider and request their electronic health data and then to share their experience. The campaign was well received by participants:

To date, over 500 people have taken part, with 51.9% of the 512 participants denied their health information. Some were told it was lost, or destroyed, some were given the wrong records, some were told they were not allowed to access it,and some were charged to do so. Of those who did receive it, 28% were given it only after follow up.

Campaign Successes

In fifteen months the campaign succeeded in propelling the issue up the public and political agenda. 200 civil society organisations took part in the campaign and quickly recognised the importance of this issue:

Over 2000 people engaged in campaign activities, met their MPs and went to request their health data at their local health facility.

Partners engaged 97 MPs who showed great interest in the issue, and agreed to take the issue forward in their respective legislatures.

The campaign was covered 45 times in the media, including on national television, national radio and in newspapers.[8] In East Africa alone over6.7 million people were reached by the campaign.

Conclusion

The digital transformation of health systems to accelerate universal health coverage and guarantee people’s right to health is premised on the collection, management, use, storage, and disposal of accurate and complete personal health data. To achieve this, clear rules and regulations based on common standards to enable the exchange of data within and across borders for common good purposes, while guaranteeing personal privacy and security, are needed. People also need more personal control over their health data.

Transform Health is calling on governments to publicly support the development of a set of minimum core components for the governance of health data, set out in a global framework, for endorsement through a World Health Assembly resolution.

Health data governance is an issue people care deeply about once they become aware of its importance and significance to themselves and to the health and wellbeing of the population. The MyDataOur health campaign will continue to build this personal and political awareness and press governments to take action on this critical issue. Find out how you can get involved here!

[1] Transform Health conducted a survey of over 2000 people in which 88% of respondents were unaware whether their health data was protected by law.

[2] This point also came through in a number of interviews conducted by Transform Health.

[3] The MyDataOur Health campaign invited people to contact their health centre and request their health data. Most participants reported that they did not receive their health data, the main reason cited was staff unsure about the request, or just refused to provide the data.

[4] Health data governance is understood as the laws and regulations that establish the rights, responsibilities, duties and obligations of those collecting, storing, using and disposing of data, national authorities, and data subjects

[5] For more information see the results of the Benchmark report on East Africa and on West Africa

[6] For more information see the results of the Benchmark report on East Africa and on West Africa

[7] Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Bening, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Ghana.

[8] Samples of the media coverage: TBC Television News; TBC FM; Citizen; The Daily Nation; East African; Daily Monitor; The New Vision (on patient access to data; The New Vision on MPs concerns over the handling of personal health data; UBCTV; Radio 1 FM Uganda; The Monitor; KFM radio, the country’s most popular station; New Vision; Agence Ivoiriene de Press; Gwediawayem FM; Radio Communautaire Guédiawaye FM; Radio Oxyjeune; Le Potentiel; News Sosedo; 5/7 Matin

My